Trigger warning for a discussion that focuses upon the venomous misogyny, including sexual violence, that featured in mid-70s issues of Ironjaw.

continued from yesterday’s blog – here – on the detestable content of Atlas Comic’s Ironjaw #1

On the comic’s final interior page is an editorial feature entitled the world of IRONJAW. In it, we’re told that Ironjaw is “unlike most other comic book characters, a real human being. What he thinks, what he says, how he reacts are all gauged by what Mike (Fleisher) feels a real man placed in the same situation would do”.

It is the single most poisonously explicit expression of rape culture that I’ve ever seen in a mainstream American comic. If the Conan of the period was frequently and undeniably misogynistic, then what can be said of this by comparison? If only the story in some way contradicted the editorial’s words. After all, it could be that Fleisher was being misquoted, or perhaps being taken out of context. But, no. The story and the hype-fluff are both singing from the same rancid wellspring. According to Fleisher, and as sanctioned by his editors, publishers and the Comics Code Authority, “real” men would always opt to be rapists, if they were lent the power and freedom to be so.

But who is the “real man” that Fleischer was referring to, and what was the “same situation” that he imagined would make rape inevitable? There is nothing “real” about Ironjaw himself, from his absurd metal jaw to his superhuman strength. Nor is the sketchy, generic setting of the tale in Ironjaw #1 in any way realistic, or, indeed, even convincing. (The world-building on both Fleisher and Sekowsky’s part is entirely facile.) As such, the argument of Fleisher as channelled through Atlas’ editorial pages is not that “a real man placed in the same situation” would commit rape, because no such man and no such situation has or will ever exist. Instead, the argument is in essence much simpler, if no less pernicious: men rape when men can. And, as Fleisher’s script for Ironjaw underscores, and as discussed here yesterday, the brutalised survivors of that violence will then respond with adoration and commitment.

In May 1980’s The Comics Journal #56, Fleisher told interviewer Michael Catron;

“A lot of people think that a story is the place to be a good citizen, The place to be a good citizen is in your life and in your behaviour. That is, you should try your best to be a good person and to treat other people well. When I sit down and write a story, I’m not out to prove I’m a solid citizen. I’m out to write a moving, gripping, exciting, sometimes gripping story … I just mean that that a story is an arena for the expression of real feelings, and not for the expression of platitudes or the feelings you think people ought to have.”

From the perspective of the blasted politics of 2019, it’s clear that there is no such thing as a story that exists in a moral vacuum, that spins a narrative and yet somehow doesn’t contribute to society’s broader debates. Stories, and often the vilest and most pernicious of stories, have proved to have an influence that exceeds any measure of truth, of reason. And in Ironjaw, what Fleisher provided wasn’t just a story with a violently sexist protagonist. Rather, Ironjaw is enmeshed in a tale that directly expresses the values of the very worst forms of toxic misogyny. When Ironjaw kidnaps and rapes a helpless woman, she falls in love with him. The very worst of raptorial uber-male behaviour is rewarded as fully as the script’s ingrained chauvinism can express.

Again, from the Catron interview;

“There’s a lot of antagonism between the sexes. There’s alot of antagonism between the races. I am not free of these feelings. I try in my life to behave as well as I can. In my stories I give free expression to my feelings. It may be that those feelings are disturbing to people who probably have those feelings too, and they don’t want to have to face them.”

This conviction, that other people, and in particular other “real men”, think as Fleisher did is a profoundly narcissistic one. In essence, Fleisher is arguing that he’s no worse than anyone else when it comes to his specific prejudices, while patting himself on the back for the honest and daring expression of that bigotry in his writing. It is a degree of toxic solipsism that doesn’t just excuse any thought, feeling or action, but elevates them to an unimpeachable standard of absolute virtue. That others might not share his view. That his views might be open to question. That it might be better to not express himself in a form that reinforces the worst of us. None of this sat with Fleisher’s self-congratulating world-view.

And so, when suffering comes to Ironjaw, it occurs because of women. When Ironjaw and Olivia’s hiding place is discovered by a young boy shepherd, she exhorts her barbarian beau to spare the child’s life. When the lad quite understandably betrays the presence of the brute who had been but a second away from cutting his throat, Ironjaw, as he’s led off to captivity, absolves Olivia of any blame.

Ironjaw: “It is not your fault! It is mine! The fighter dies young who heads the counsel of women!”

And death it almost proves to be, in the ethical closed-loop of Fleisher’s macho paradise. Women, the message is clear, should be raped, but never listened to. It’s a policy that Ironjaw follows when, condemned to a dungeon, he, unknowingly, encounters his own sister. Assuming, wrongly, that she’s been sent for him to rape in the long hours before his execution, and never bothering to ask whether that’s actually so, he has to be beaten off his prey by a handy nearby jailer. Obviously, sexual violence imposed upon close family members, even unwittingly, was a step too far even for Fleisher’s internal “darkness”. But in that flash of supposedly arousing material for the ethically challenged bloke-reader, Fleisher does take the opportunity to express a few other key sexist tropes;

“The women in this god-forsaken kingdom are the same as women everywhere! First they offer themselves to you on a platter, and then they (refuse you)”.

In his 1980 Comics Journal interview, Catron put it to Fleisher that “some people have said in your writing there is a certain resentment being expressed against women”;

To which Fleisher responded; “It’s possible”.

To be continued tomorrow, with a look at Atlas’ Phoenix, its first superhero title. A return look at Ironjaw, and in particular Fleisher and Sekowsky’s worldbuilding, may well happen before the end of this month’s posts …

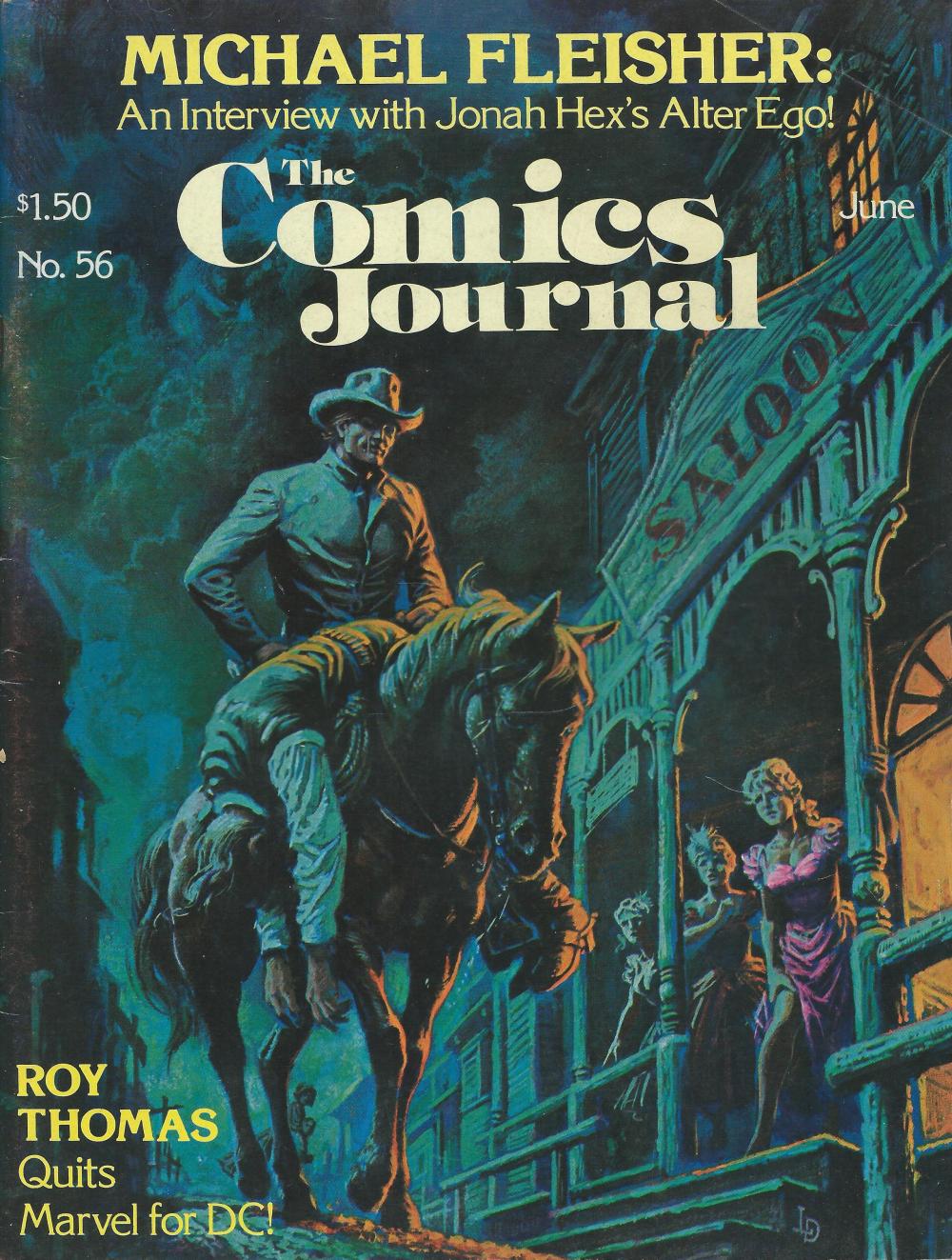

Aha, you also noticed that creepy text page business. That Comic Journal interview is pretty enlightening… and what a cover. I only know Luis Dominguez from his work on DC’s mystery mags, especially Ghosts, and this Jonah Hex image is richer again. I’m OK with a tiny bit of leg from a bawdy bar-room gal, presumably she wanted to entice the odd cowboy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Martin – I think that LF’s cover’s tremendous. And my objection to the leg-showing isn’t an absolute one. It’s just that it makes no sense in the context of the cover itself. The composition draws attention to itself there in an awkward manner, which is a shame, given how tremendous the rest of the work is.

LikeLiked by 1 person