continued from here:

Vicki was in many ways the most traditional form of comicbook that Atlas ever published. For wasn’t that how the form itself began in America, with thick collections of cheaply acquired pre-existing material sold to young readers with new eye-catching covers? Without access to Seaboard/Atlas’ sales figures – which I would dearly love to have! – it’s impossible to say how profitable the strategy was in 1974/5. Perhaps it’s telling that Vicki was one of the six Atlas titles to reach a fourth issue before the company itself collapsed. But looking back, it’s interesting to note that Archie Comics, upon whose toes Atlas was of course stepping with Vicki, prospered in the declining marketplace of the Seventies with a quite different strategy. The future of the American comics industry would follow very different rules to those which Martin Goodman had followed so profitably since 1939.

It’s tempting to wonder whether Martin Goodman and/or his colleagues had noticed, when they decided to go ahead with Vicki, that both Marvel and DC had already discontinued their teen comedy comics? In essence, the Big Two had already ceded that particular niche to Archie. Did those at Atlas ever note that Marvel’s Millie The Model had ended in the summer of 1973, and that DC had tipped both Date With Debbie into the ground in the autumn of the previous year? Did Goodman Snr see that as somehow leaving space for Vicki to cream off the relatively small degree of Archie’s sales that the Big Two had abandoned, or had it all passed him by? It would be fascinating to know how he thought he could prosper where the two most powerful comics publishers of the day had faltered. Surely if either of the Big Two had seen a profit to be turned with cheap reprints of teen comedy tales, they would have repackaged their own archives and got on with turning a penny or two?

Like every publisher of the period, Archie Comics saw its sales plummet. According to Comichron, Archie itself had seen its total paid distribution figure of half-a-million copies in 1960 almost halved by the arrival of Atlas in late 1974. Yet the company was still in rude shape, and especially so in comparitive terms, with few superhero titles beyond Superman and Spider-Man coming close to Archie’s top-of-the-range titles. Most importantly, the company was developing an alternative strategy to newsstand sales. To look at the titles being issued by Marvel and DC Comics during the period is to register an exhilerating spread of different publishing formats, each seeking to generate greater profit than the few pennies earned by the tradional monthly pamphlet form. So low was the return on the standard-issue comicbook that there was very little incentive for newsagents to sell them. The holy grail for the comics industry, or so it was often thought, would be a format that offered more story pages while charging a considerably higher price. (It might also be an approach, some argued, that would also allow adults to be targetted with a more substantial, if reshaped, product.) And so, in the very month that Vicki appeared, DC published seven 100 page titles, all featuring around 20 new pages of story and art along with a mass of reprint material, such as with Detective Comics 445;

In addition, DC also published several Treasury editions, such as the mostly all-reprint Christmas With The Super-Heroes, which carried nothing new beyond a few editorial pages;

Many of the fanzines of the time suggested that sales were initially strong on these formats, and, buyoed by novelty, they may well have been. But for a variety of reasons, from the all-important matter of profit to the problems of displaying the extra-large Treasury editions, the market soon rejected anything much on a regular basis beyond the 20 page pamphlet. Two years on from November 1974 and not a single treasury or 100 pager appeared from DC.

Marvel too was pursuing alternative packaging and content strategies in the month that Vicki appeared, with two treasurys of its own being shipped, Giant Superhero Holiday Grab-Bag and Thor;

In addition, Marvel had four Giant-Sized editions on sale, quarterly companion titles to its regular monthly titles which typically featured longer new stories than the pamphlets did alongside a selection of reprints.

There was also 6 black and white Marvel magazines, aimed at a somewhat older audience and published with reference to the industry’s in-house self-censorship body The Comics Code Authority;

Yet as with DC’s experiments, all of these forms would soon fall short of Marvel’s hopes. By November 1976, only three black and white magazines of all the formats mentioned above saw print, and all of those would soon be cancelled. Larger-format publications would continue to appear from Marvel, but never in the hopeful, month-on-month numbers seen in 1974. Big had not proven to be better, although on occasion if not as a norm, it might still prove to be profitable. (*1)

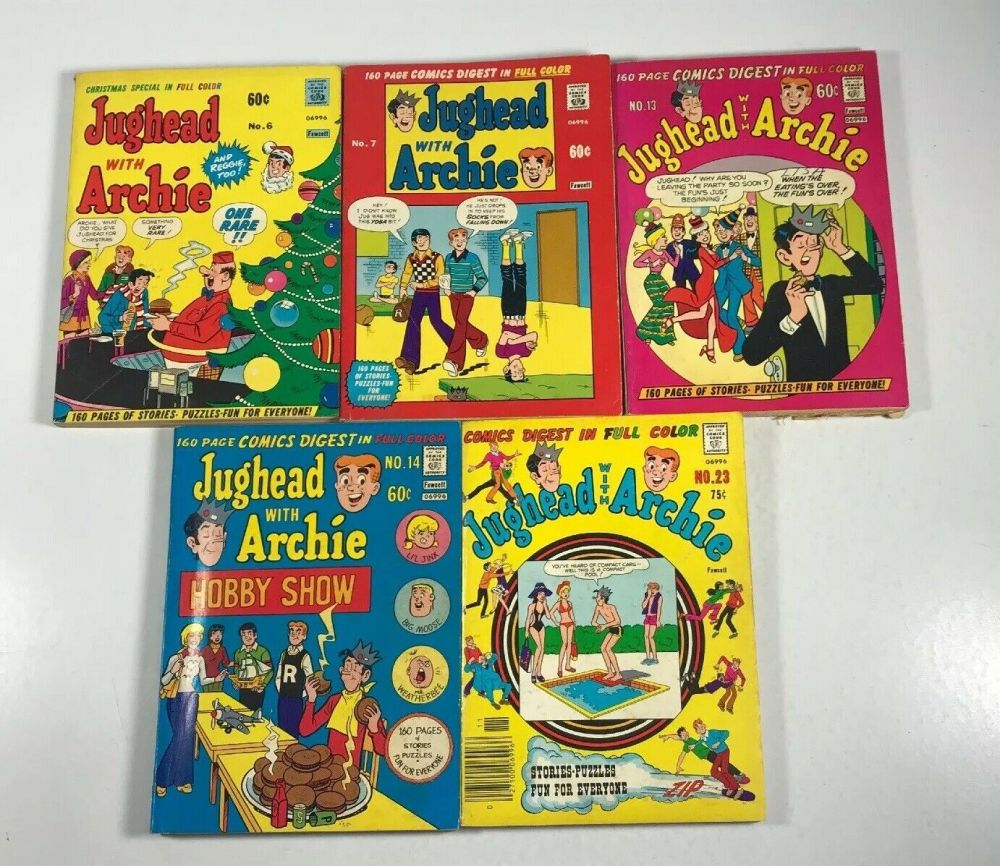

Which is why Archie Comics’ strategy for long-term survival seems, from this distance, so impressive. Because Archie eschewed the logic of bigger and more expensive, and instead, over time, pursued digest-sized collections to be largely sold in supermarkets. For all that the company would continue to publish pamphlet-sized comics in a variety of forms – there were 21 comedy Archie titles in November 1974 alone – it was the new opportunities generated through this exploitation of a lesser-used format in a largely under-exploited marketplace that would help it prosper in the years to come. It was not a strategy without up-front costs. Archie had to pay, and pay what’s been called a considerable amount, to get their titles into the rack-space nearby tills, where browsers, caught waiting, would be most likely to make casual purchases of comics.

In short, Atlas was competing with what it thought to be Archie when it published Vicki, but Archie was already beginning to move on.

*1:- For example, it seems highly likely – to say the least! – that Marvel’s Treasury-sized reprints of its adaptation of Star Wars in 1977/8 generated a truly significant profit.

Archie’s comics had a considerable advantage when it came to sales to the general public. The company had a long tradition unsullied by any concerns about the corrupting influence of comicbooks, and had even succeeded in repeatedly wrapping itself in the flag. Why, Archie Comics were practically expressions of patriotism in themselves, regardless of the subject matter at hand. Still well-known through media tie-ins, Archie’s comics offered a comfortingly conformist and colourful reading experience that seemed both timeless and, after the fashion of Saturday morning cartoons, contemporary. For parents and children being processed through the tills of America’s supermarkets, Archie’s digests made for an affordable and cheerful indulgence. If the digests cost more than twice a typical Archie comic, that fact was hardly obvious in the pay-here queues, where there were other comics to inspire a comparison of prices.

And with its decades of stories to be dusted off and reprinted, Archie was perfectly suited to supplying a seemingly endless conveyor belt worth of digest titles. Brand recognition was high, costs were low, and the company had, even as newsstand sales continued to plummet, a perfect outlet for its product. By the 1980s, Betty and Veronica digests became a particular success. The new marketplace had brought new oppurtunities, new preferences. No other publisher could compete with those comics in those spaces.

Seen in the broader context of the rest of the Seventies, Atlas’ Vicki seems like, at best, a short-term wager rather than an economically sustainable model. What did it matter that Vicki’s extra-sized issues went for 50 cents rather than the half of that that the rest of Atlas’ comics did? Yes, the prospect for higher profits was there, but was there a lasting market for such shoddy product? (Archie’s 60c digests, to my unturored eye, may have turned an greater profit than that 10c difference when lower paper/printing costs are taken into account.) Of course, Martin Goodman had made much of his fortune from moment-to-moment trend-jumping, and a publishing venture that only turned a profit for a mere month or two would have most probably not concerned him. But in Vicki’s form and content, we can see a great deal of what went wrong with Atlas Comics. Pursuing decades-old short-term exploitation strategies in a rapidly changing marketplace was not what the age called for. The Goodmans were hardly the only people who failed to grasp that the ground under them was changing, and changing dramatically, and that it would continue to do so without pause. But Atlas swamped the newsstands with mostly third-rate product, and appeared to care little for anything but immediate profit. The company was a huge gamble based on redundant practises. It would all prove to be, as events would soon underscore, commercial suicide. More canny operators had already seen something of possible paths forward that Martin Goodman, who thought of himself as the publishing brains behind Marvel’s success, had never, it appears, once even imagined.

to be continued, as 31 Days Of Atlas nears its end …

this series of blog posts is easily the best thing to have ever emerged from the atlas debacle.

“everything’s archie” indeed!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you 🙂

LikeLike