So, Seaboard/Atlas appears to have at first gone out of its way to associate its new line of comics and magazines with Marvel Comics. (See here.) And as discussed here, the initial editorial content from Atlas had insisted that their books would actually outstrip Marvel’s in terms of new ideas and, presumably, storytelling approaches. So what might a reader whose fannish sensibilities had been shaped by the post-1961 Marvel tradition think of Atlas’ stories? To take one vital example, what would a reader who’d been encouraged to think of individual tales as existing within the framework of a vast immersive fictional universe think of Atlas’ atomised and apparently never-to-be-connected strips?

Perhaps Atlas should have simply declared that it wasn’t going to create a single, tightly-policed continuity for any of its books. Then the question of how they fitted together wouldn’t ever have emerged. And yet, for a new publisher attempting to appropriate a considerable measure of Marvel’s credibility to then deny any kind of inter-relatedness would’ve surely been a self-defeating strategy. The working assumption of all but the most casual of readers would surely have been that there was at least some connective tissue that bound, say, The Cougar, with its vampire antagonist, and Son Of Dracula. That would have been the kind of issue that many of Marvel’s creators would have loved to clarify. Yet of any such world-building, there wasn’t the slightest sign. Whatever the problems of excessive continuity, the complete absence of any shared ground could come across as not merely an opportunity missed, but also as a responsibility spurned. Indeed, it quickly felt as if, compared to its Big Two competitors, Atlas simply wasn’t trying.

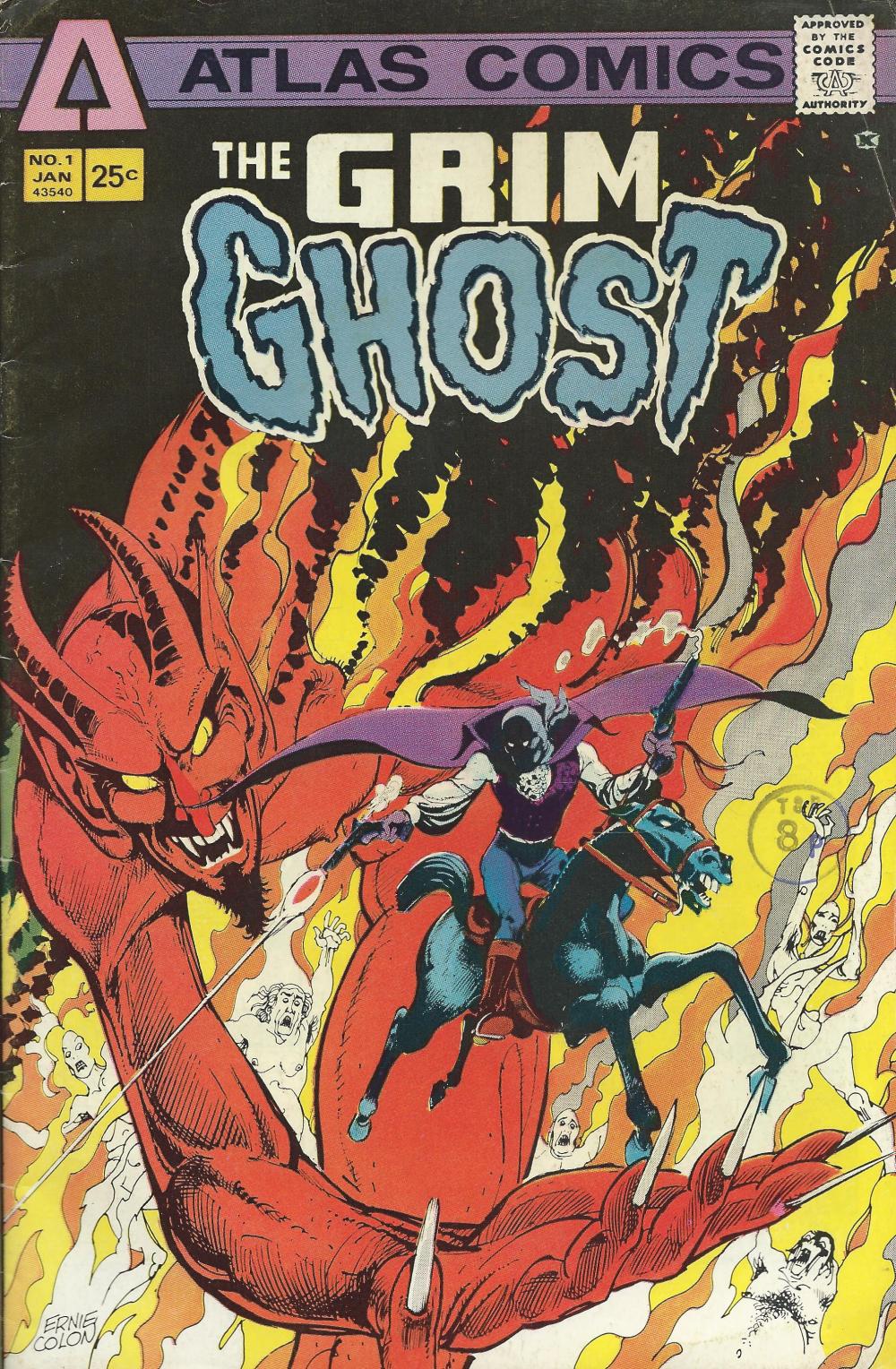

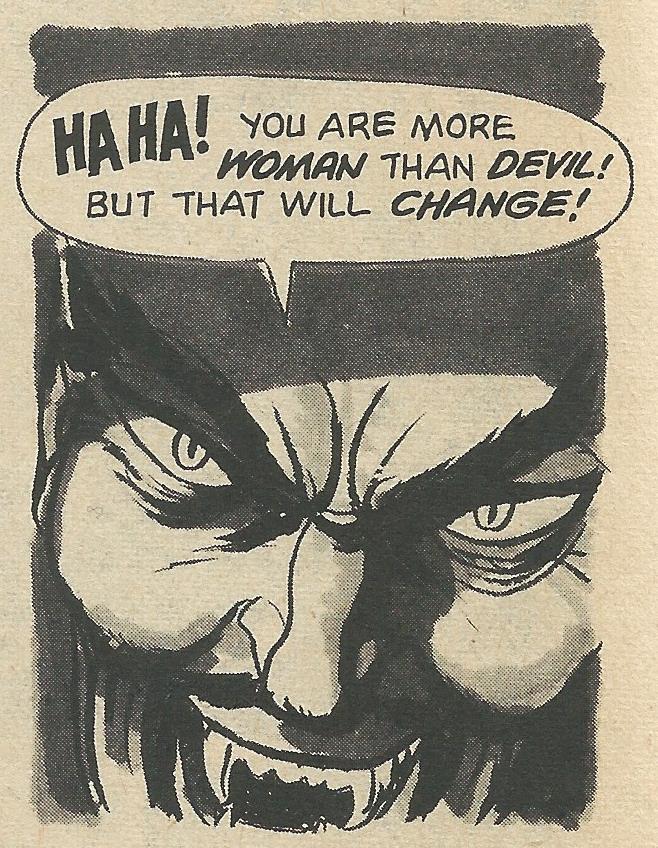

Take, for example, the figure of Satan, who appeared in The Grim Ghost #1. Released in Atlas’ first wave of three comicbooks on November 12th 1974, the tale quickly established The Devil himself as the new strip’s major antagonist. Here he is, as portrayed by artist Ernie Colon and writer Mike Fleischer;

Naked, cloven-hooved, pointy-eared and the possessor of a rather endearing little fluffy tail, this Satan appears to take a considerable degree of enjoyment from his responsibilities. Intimidating but with a sheen of charm, Satan offers the damned soul of 17th century British highwayman Matthew Dunsinane an enticing, if nonsensical, offer: the newly hung criminal can return to the Earth and murder “evil people” in order to keep Satan’s torturers supplied with a sufficient number of sinners, or Dunsinane can take his place in the ranks of the eternally tortured. It is, of course, no choice at all, although why Hell can possibly be afflicted by an excess of torturing demons and a deficit of damned souls, or indeed why Dunsinane, with the present of a flying horse, is the best way of swelling the underworld’s population of sinners, is never explained.

Yet just two weeks after the debut of The Grim Ghost, Atlas’ Devilina #1 features what appears to a quite different Satan. This Lord of the Underworld is in form indistinguishable from an ageing and yet statuesque human male. Instead of hooves and a tail to indicate his demonic nature, he relies on costumery to signal his fiendishness. With his particularly high collar, a cape, what appears to be a cowl through which his horns protrude, and skin-tight underwear held up by a belt with a large skull-shaped buckle, he is both a more irascible and, at moments, more emotionally vulnerable Beast. As written and drawn by Ric Estrada, whose broad similarity of style to Ernie Colon’s work makes the tale feel as if it really could share a universe with The Grim Ghost, “Devil’s Doman” lends Satan a mother, with a recently born sister, who opts, out of shame, to flee Heaven for Hell in the wake of a “Rebellion Of Angels”. (To tease out what that all says about the celestial kingdoms in Devilina would appear to demand a later return here to the short-lived series.) Somehow appalled by the prospect of his tiny sister growing up in Hell – “I shan’t allow this corruption and evil to touch you — or the child!” – Satan transports mother and baby into the “future … a mansion by the sea of the New England shore”. There, he declares, his family can be safe, with the young Devilina being brought up to learn “sorcery, Necromancy and magic”, all of which appear to be the same thing. As the tale continues and Devilina grows into an of-course attractive 1970s teenager, Satan re-emerges as a murderously intrusive and over-protective father who ends up immolating Devilina’s first boyfriend.

The two Satans appear to quite separate characters, both in terms of appearance and character. Yet it wouldn’t be in any way difficult to reconcile the one with the other, and now, as then, it does seem a waste to have The Grim Ghost and Devilina in quite separate worlds when both might benefit from the extra narrative texture lent by a shared back-story. By what appears to be chance, the two Satans both have a taste for hard-to-rationalise time travel. In The Grim Ghost, Dunsinane is hoisted in the 20th Century because there’s apparently so much more evil there. In Devilina, Satan also magiks his self-exiled mother and sister from pre-history to a life in the mid-Seventies, although why he does so goes entirely unexplained.

If the intention of Atlas was indeed to keep its strips entirely apart, then a greater editorial attempt to keep their comics from so obviously trespassing on each other’s territory would surely have been a judicious choice. To not operate a common continuity is a perfectly valid choice. But to do so while throwing up a series of hints and common situations was to misdirect expectations and encourgae bafflement. Even were it to be a given that the material in the company’s magazines, which went to press without the Comics Code Authority stamp, and its comics, which somehow acquired the CCA’s authority, were never to crossover, the similarity of situations and characters would still suggest that a common universe was being established.

And once that suspicion is encouraged, then any scrap of possibly-relevant information can appear to be evidence of a greater plan of, or, at the very least, a broader potential, as in this page from the second-ever Seaboard publication, Weird Tales Of The Macabre #1, from October 22nd 1974;

In “A Second Life“, an eight-page potboiler by Ramon Torrents, a drowned young woman returns to life, having previously made a deal with Satan to be resurrected in order to “know love .. to forget hate!”. It’s a plot device to make the head spin, since why anyone would seek out the Devil before they died and ask such a favour, or indeed why Satan would grant it, is impossible to deduce. (What could possibly be in it, given what we’re told, for the Devil?) Yet the Satan of The Grim Ghost had himself shown a taste for bringing back to life the horribly deceased, and without any kind of rational explanation for doing so either.

Both in the supernatural-themed books and beyond them, there was the illusion of a shared narrative tapestry in Seaboard/Atlas’ magazines and comics, an accidental overlapping of popular traditions approached with both enthusiasm and carelessness. And since the existence of such a common backdrop hadn’t been ruled out to readers, and given the several suggestions that Atlas was moving in Marvel’s storytelling slipstream, an inevitable sense of, at best, a lack of ambition hung over the company’s books from the very start. Well, why wasn’t this potential being exploited?

Marvel would have done so, to a lesser or, most probably, a greater degree.

***********

And then, as the months passed, the problem across the Atlas line merely intensified, until the arrival on June 3rd 1975 of the company’s penultimate title, Demon Hunter #1, which delivered a set-up of a demon race and a secret society that made no mention of Satan at all, whether with a tail or not. Hell and several of its leading demons were, by contrast, most certainly a presence in the Rich Buckler/David Anthony Kraft tale.

Confusion would have most probably been even further intensified, had Seaboard/Atlas not, with the release of one last single comic, not collapsed and disappeared entirely from view.

*Please don’t let me end up suggesting that a lack of a common continuity amongst a publisher’s books can’t be a darned good thing. Of course it can be.

31 Days Of Atlas Comics will return tomorrow …

The art on that page from Grim Ghost is rather good Colon – the only Atlas work of his which I’m familiar with is Tigerman #1, which has some of the lousiest layouts I have ever seen (I thought it an ill omen that no one was willing to have their names appear in the credits for Tigerman #1).

LikeLike

I’d agree entirely on the virtues of Colon’s art for Grim Ghost #1. Best of all, and I’m certainly coming back to this, is his depiction of horses, whether in Georgian England or flying absurdly and wonderfully across the sky of a 20th century city.

I haven’t spent much time at all in the company of Tigerman since it was published back there in decades-ago-land, but you’ve made me want to read it now. (And clearly it’s on my must-reread pile for these pieces.) By chance, I was reading an old Atlas editorial page this morning that declared Tigerman was the most powerful of the company’s protagonists, which did bring me short. Really? I shall go and investgate the matter, re: power and art and credits, immediately 🙂

LikeLike

Oh dear, you haven’t re-read Tigerman yet? One does not simply walk in to Tigerman…

I reviewed all three issues of Tigerman for my blog… in fact, I think my review of issue #1 is the best review I’ve ever written – I don’t always find it easy to talk about artistic choices in comics, but the layouts in Tigerman #1 are so bad it gave me quite a bit to say, to the point that I even made a diagram to show how poorly the panel-to-panel flow of Colon’s fight scenes were constructed.

LikeLike

I reread Tigerman this very evening. And it is indeed an absolute stinker. There are brief moments when Colon’s art sparks into life. A night time single panel shot of the city. And, er … OK. There is a brief MOMENT.

I shall be chasing down your blog posts post haste. There is, almost unbelievably, a want of top-notch Tigerman reviews on the net in 2019. 🙂

LikeLike

So many devils! Atlas really does seem to have been a big old mess. I do like the smooth naked devil, of course.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now you’ve done it. Now I’ve started ranking my favourite devils. Who knows where this will end, or indeed when? 🙂

LikeLike