In which the blogger, intending to write a little about Jack Kirby’s 1958-1970 career at Marvel Comics, attempts to gain a little perspective on the storyteller’s work immediately before his return to what he’d help transform into ‘The House Of Ideas’.

To go by the titles published in the mid-summer of 1958, Jack Kirby would appear to have found a secure and prosperous niche for himself in a tumultuous time for the comics industry. July’s newsstands featured five titles alone from DC Comics, cover-dated either August-September or simply September, that hosted Kirby’s storytelling. House Of Mystery #78, House Of Secrets #12, and Challengers Of The Unknown #3 each featured a cover with Kirby’s pencils and inks. (On the later, his wife Roz contributed with the filling in of solid blocks of black.) Within the Challengers’ third issue, Kirby also definitely contributed pencils for two 12 page tales and may well have helped, to a greater or lesser degree, with those story’s scripts. For House Of Mystery, he illustrated, and may well have written, a 6 page alien-invasion pot-boiler entitled The Hole In The Sky. Elsewhere in the DC line, two 6-page Green Arrow tales by Kirby appeared, one in Adventure Comics #252 and one in World’s Finest Comics #96. For each, he produced, with his wife’s assistance, both pencils and inks.

It couldn’t be said that Kirby had been assigned to DC’s most prestigious titles. Having spent most of his career as the commercial spearhead of whatever line he was contributing to, Kirby was now regarded by some powerful figures as being firmly ensconced in, at best, the second division. (He would soon come to be regarded by DC as being entirely dispensable.) By contrast, Curt Swan, who worked as a young artist on Kirby’s strips with Joe Simon during the war years, had 5 covers on books for the Superman and Batman franchises on the stands in July 1957. He also had 36 pages of pencils published during the same period. An undeniably fine comics artist in his own right, Swan was, however, no Kirby, either in terms of storytelling or invention. But the wheel had turned. Artists who’d once been Kirby’s assistants, or whose career was in major part based on his work, were now far ahead of him in the pecking order.

But in a deeply depressed and ever-shrinking marketplace, DC – even if it clearly no longer regarded Kirby’s storytelling be commercially or artistically of the first rank – appeared to offer a relatively lucrative berth. To have 3 covers, 42 pages of pencils and 17 of inks, with perhaps some measure of contribution to 29 pages of scripts, ensured a living denied to many of the age’s comics creators. (*1) To the likes of John Romita and John Buscema, who’d been thrown of work by the relatively recent collapse, and near extinction, of Atlas Comics, Kirby’s workload must have looked enviably profitable.

*1: I’m hoping I’ve got these figures right. If I haven’t, it’s not the fault of the two excellent sites that I’ve relied upon the most here, the Grand Comics Database & Mike’s Newsstand. Whatever the flaws in my maths, I hope a truth is being told in general if not precise terms.

Of course, the presence of an artist’s work on the stands in any particular month doesn’t mean that it had all been produced at the same time. Judging an artist’s success by what appears in any one four or, in effect, five week period is always an undeniably imprecise measure. (During the same period, Atlas/Marvel survived through publishing little but inventory stories while commissioning but a small amount of new material.) But I believe this snapshot of July 1958 tells a truth about the moment for Kirby, if not about its immediate aftermath. For he was undeniably doing rather well out of DC. He had lost the autonomy that he and Joe Simon had put to such good use until the collapse of the comics market, and subsequently their partnership, in the mid-50s. With that had gone a considerable degree of economic clout and reward. But in what would amount to around two years at the DC Comics during the period, Kirby would still sell the company more than 600 pages. As Mark Evanier has written, that evened out at less than 20 pages a month, which, for the prodigiously productive Kirby, was only a fraction of what he might have been called on to create. Still, when a court case with DC editor Jack Schiff later came to trial, Kirby’s annual income during the period was claimed to be well in advance of $8000. If true, and in today’s terms, that would put Kirby’s income in 1957 at around $77 000, and in 1958 at $73 000. It was, by most people’s standards, a very good living in an era when the average wage was less than half of what Kirby was said by Schiff to be earning. In Ronin Ro’s Tales To Astonish, for which the author appears to have had access to original trial documents, Kirby is said to have claimed that he’d earned considerably less than that, and that his income had recently catastrophically declined as a result of his dispute with Schiff. Whichever figure is accepted, Kirby would have been have earning, in 2018’s terms, more than $43 000 a year. Of course, neither his or Schiff’s figures represent anything close to what Kirby’s work was worth, or indeed, would prove to be worth over the coming years. Even 70 years later, his Silver Age stories are still being profitably collected by DC. But for all that the company was failing to adequately reward his work during the late Fifties, his income from them did permit a comfortable standard of living.

Of course, Kirby wasn’t just working for DC. In the same July, he also saw work printed by the publishers Crestwood/Prize and Harvey. For the former, he produced the pencils and inks for both the cover and a 5 page story for Young Romance #11:5. It was the very comic with which he and Joe Simon had, in effect, created the American romance comic in 1947. Now in decline, it had at its peak shifted millions of copies. The indications are that Kirby was, at this point in his career, growing ever-more weary of the genre’s form and content in the comics of the time. In addition, he can hardly have been overwhemingly happy with working for the company which he’d accused just four years before of stealing $130 000 from himself and Joe Simon. Still, with a wife, three kids and a mortgage, it’s to be supposed that the regular and undemanding gig was a useful, if comparatively minor, source of income. As any number of sources have contested, Kirby was driven by an absolute determination to provide for his family. That same unambiguous, primal motivation would see him soon return to what we now know as Marvel Comics, despite his distrust and dislike, in varying measures, for the company’s publisher Martin Goodman and its editor Stan Lee.

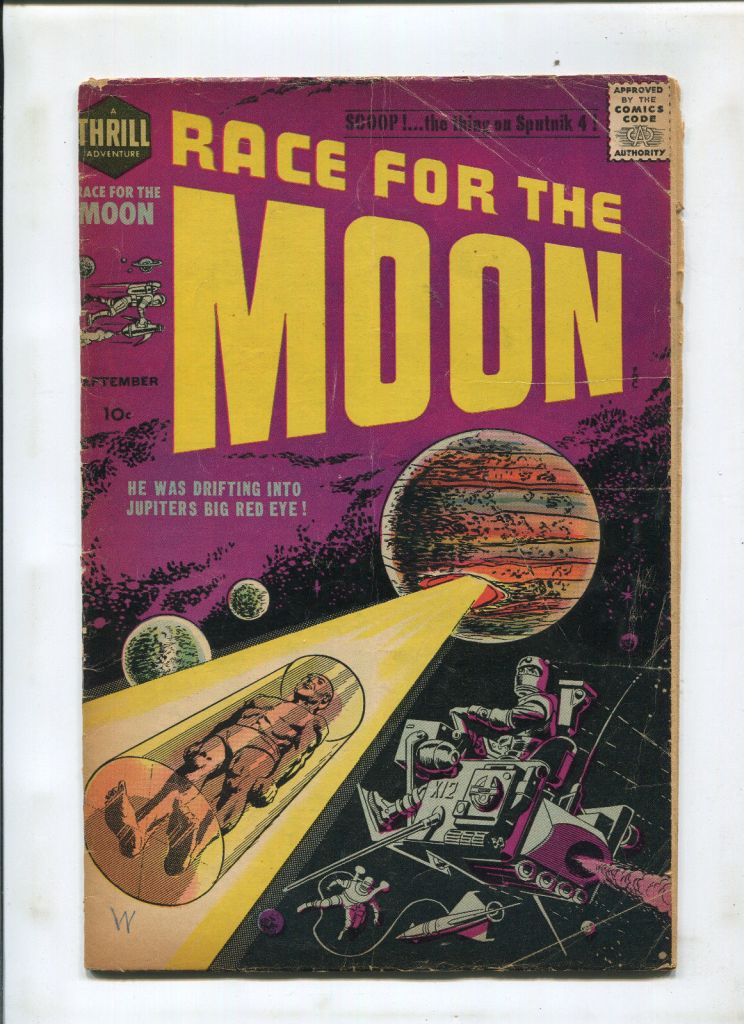

For Harvey in this month, Kirby contributed substantially to the still much-admired Sci-Fi anthology Race For The Moon. In the wake of Sputnik and with the Soviet Union’s dominance of outer space, the conquest of the void was a subject of massive public interest and, indeed, existential unease. For the second issue of the title, Kirby provided pencils for the cover and 22 pages of art for 5 separate features behind it. (It’s also known that he contributed at the very least 5 pages of script for the issue, and perhaps many more.). As inked by Al Williamson, the result was a remarkable fusion of Kirby’s dynamism and invention and Williamson’s illustrative, elegant finishes. The splash page of The Face On Mars, to take but one example, radiates a sense of trippy cosmic grandeur that, after its own fashion, remains every bit the equal of the likes of Druillet and Moebius’ later psychedelic-infused Sci-Fi strips. In addition, Kirby provided the pencils for the cover for Harvey’s Warfront #34. (*2)

*2:- The contrast between the form and content of Kirby’s work for DC and the results of his assignments elsewhere during this period is something I’ll return to, as best I can, in a later post. For the purposes of this opening piece, I’m focusing more on Kirby’s versatility and productivity while trusting that the reader will take the overall quality and worth of his storytelling for granted.

As if that wasn’t work enough for Kirby to be attending to, there was also the daily syndicated Sci-Fi strip Sky Masters Of The Space Force, which Kirby was driving forwards towards its September 8th debut in 300 newspapers. As with, ironically, Stan Lee and his 1958 collaboration on the strip Ms Lyons Cubs with the artist Joe Maneely, Kirby, with the writers and brothers Dick and Dave Wood, was hoping to break successfully out into the far more richly rewarded world of newspaper strips. (It was hardly Kirby’s first attempt at a newspaper strip, a field that he’d regretably never succeed in conquering.) Another attempt to tap in the Cold War zeitgeist, Kirby’s storytelling in Sky Masters – which would also at times include aspects of scripting and colouring – was ingenious and compelling, complimented as it was at first with Wally Wood’s richly polished and beguilingly romantic inks. But the strip never succeeded in catching the public’s imagination. Worse even than the unaffordable drain of time and energy and emotion it soon proved to be, the strip would also generate a catastrophic degree of life-changing ill fortune for Kirby. Arguments over both the source of the strip’s contents and the distribution of its relatively meagre profits would cause Kirby and DC editor Jack Schiff to fall out in ways that were, for the former, both financially and professionally disastrous.

As if that wasn’t work enough for Kirby to be attending to, there was also the daily syndicated Sci-Fi strip Sky Masters Of The Space Force, which Kirby was driving forwards towards its September 8th debut in 300 newspapers. As with, ironically, Stan Lee and his 1958 collaboration on the strip Ms Lyons Cubs with the artist Joe Maneely, Kirby, with the writers and brothers Dick and Dave Wood, was hoping to break successfully out into the far more richly rewarded world of newspaper strips. (It was hardly Kirby’s first attempt at a newspaper strip, a field that he’d regretably never succeed in conquering.) Another attempt to tap in the Cold War zeitgeist, Kirby’s storytelling in Sky Masters – which would also at times include aspects of scripting and colouring – was ingenious and compelling, complimented as it was at first with Wally Wood’s richly polished and beguilingly romantic inks. But the strip never succeeded in catching the public’s imagination. Worse even than the unaffordable drain of time and energy and emotion it soon proved to be, the strip would also generate a catastrophic degree of life-changing ill fortune for Kirby. Arguments over both the source of the strip’s contents and the distribution of its relatively meagre profits would cause Kirby and DC editor Jack Schiff to fall out in ways that were, for the former, both financially and professionally disastrous.

So, in that single summer month in 1958, Kirby had, in total, 6 covers on the stands, including 4 which he either inked himself or with Roz Kirby’s help. In addition, 69 pages of pencils, with at least 22 of them featuring his and on occasion Roz’s inks, appeared in print, along with an indeterminate, but perhaps substantial, amount of scripting too. There was also a surely considerable degree of work undertaken on Sky Masters. This storytelling involved a whole range of genres, from action-adventure tales hybridised with the superhero and space opera traditions to romances, war stories, and fantasy/sci-fi-tinged thrillers. From the perspective of 2018, Kirby was clearly the most valuable player in 1958’s comics industry. Sadly, several of those in positions of power at DC Comics would soon prove to be in possession of a quite different point of view.

As I intend to come to, Jack Kirby’s position on America’s newstands would no longer seem so promising by the time Christmas 1958 rolled around. By the summer of 1959, Kirby’s career would be taking a quite different, and most certainly less financially rewarding, path. Ahead was the Marvel Revolution and the beginning of a culture-changing shift in the nature of America’s action-adventure storytelling. But as yet, all of that was a very, very long way ahead. Even Kirby, who’d often prove to have a pretty good sense of where the times were headed, wasn’t able to see anything of that utterly unexpected paradigm-shift that we now know as the Marvel Revolution.

to be continued, with a look at Kirby’s reluctant return to Atlas/Marvel, a move which must have been underway in the very month discussed above;

That Sky Masters page reminds of the cast of the contemporaneous Dan Dare strips in the UK, which were similarly wowing 50s kids with their tales of basically WW2 heroes in space. Although in the British version had the lone female character as a scientist (Professor Peabody) rather than just the daughter of one of the characters.

It’s also hard to believe that the Soviets were only 5 years away from sending the first cosmonaut in space when that comic came out.

LikeLike

Sorry, I mean ‘first female cosmonaut’, of course!

LikeLike

‘Dr Royer’… interesting coincidence, that’s not a common name, is it? Maybe Kirby Inker Mike Royer is an Earth Prime relative?

Anyway, fun piece, very informative, I never knew Roz Kirby spotted blacks or whatever.

Re: ‘But for all that the company was failing to adequately reward his work during the late Fifties, his income from them did permit a comfortable standard of living.’ Is this not a bit of 20/20 hinsight?

LikeLike

I hadn’t thought of the Royer/Royer connection. It’s a good spot!

I’m learning about Kirby’s work in this period myself. So although I’d heard Roz Kirby contributed inks during this period, I most certainly didn’t know where and in any way to what degree, But I have recently read a couple of interviews – one at TCJ, one at TJKC – in which he speaks very highly of her work. As of course he would, but he certainly seems to have trusted her on assignments that the Kirby family really couldn’t afford to lose.

I hope I’ve caught your sense about 20/20 hindsight in what I write beyond this point: while it’s true that DC couldn’t have known that Kirby’s 1957/8 work would still be so successful 70 years later, they were a business grounded in a deliberate and forceful policy of denying their creative staff their rights on any number of levels. It was company policy to make sure that it owned whatever it could get its mits on and with the greatest possible degree of corporate advantage too. When it comes down to working conditions at DC, there was, as of course you’ll know, no health care, no protection from workplace bullying, no rights to intelectual property or artwork, etc etc. (Gawd, their fortune depended on Seigel and Shuster’s Superman, but they treated the former terribly and ignored the latter entirely. And of course, the company’s fear/anger at talk of DC creators organising in the 60s led to a mass claerout of staff, no matter how long and loyal their service.) So DC were 100% exploitative. If they paid more than most, if not indeed all, of their rivals, it still wasn’t much in comparison to all that they took. I guess what I’m saying is that, although DC couldn’t know that the Challengers etc would still be in print, they made damn sure that any such possibility was secured to the company’s maximum advantage. And of course, the higher up in the company the DC shirt’n’tie men, the more the company’s advantage became theirs.

It IS amazing, that those Kirby Green Arrow tales should have been reprinted in at least 4 seperate collections since around the turn of the century. No-one could have foreseen that. But the company made sure no-one else but itself would benefit from those stories after Kirby’s initial work for hire payment. Gad sir, it fair makes my blood boil.

ATB

LikeLiked by 1 person